As an amateur pharologist, visiting lighthouses is one of my favorite things in the world. The rough collection of run-on sentences here will hopefully be of interest as I slowly work to recall the dozens of stations I've visited over the years.

Vietnam and Taiwan (Content Warning: No Lighthouses)

January 5-19, 2025

Sunday, January 5th

We took a Starlux redeye from Seattle to Taipei, which might have been the most comfortable flight I’ve ever taken had we not timed our transpacific venture with the 2025 International Crying Babies Convention that Taiwan was hosting. I can say I didn’t sleep like a baby— I slept like a grown man whose friends kept him up too late on New Year’s Eve, thankfully enough— so I didn’t have to tap into the dozens of entertainment options I always prepare for myself but always lose interest in once the plane hits altitudes that resemble the height I have set on my Hinge profile. The Taipei connection was brief, spent in a lounge a bit too crowded to really be called a lounge, and we were off to Hanoi, this flight spent in the endearing company of John Green.

I hoped to warm up my Chinese with some of the friendly looking people my age that were on the plane, but I was placed between two Taiwanese women enjoying the freedom of travel that comes with being 85. I offered a 早上好 to one of them. She gave me the same look she probably gave Mao Zedong when he proposed the cultural revolution. 好, she answered curtly. The flight felt long.

Immigration into Vietnam felt longer still. Outside the airport, we immediately spotted a man holding a sign with Andrew’s name— an easily fooled man would assume him our driver, but Andrew is not easily fooled.

“Andrew, I think this is our guy,” Jungwoo called as Andrew briskly walked past the man.

Andrew hissed in return, “This guy is at pillar 10, the text our real driver sent me said he’d be at pillar 11. It’s too early in the trip to be falling for obvious scams.”

We checked pillar 11. Empty. Sheepishly, Andrew returned to the man Jungwoo was now standing next to. In a shock to everyone, he drove us to the hotel without committing a single kidnapping.

The hotel desk was quite friendly, and Andrew’s south Vietnamese rizz not only procured us a pair of room keys but her phone number and a long text of recommendations for Hanoi and some of the other cities we planned to visit. Nice. We washed up quickly and returned to the streets.

For the first time, I was able to really ingest the absolute miasma of action that is a Hanoi street. The treeroot-snaggled sidewalks are densely covered in scooters wherever a small business is not, forcing pedestrians into the street where they were joined by more scooters, cars, buses and bicycles, not a single one respecting the concept of a lane. Narrow buildings are packed tightly together, uneven and multicolored like a British man’s teeth, many presenting a flag flickering the single Vietnamese star or a hammer and sickle. Every smell imaginable, most of them bad but some of them good, shared the air with the loudest and most tonal of the spoken languages. Goldfish memory drivers compulsively reminded themselves whether their car horns still worked. Flocks of scooters, 3, 4, 5 vehicles wide and 6, 7, 8 vehicles deep moved like a hive mind and spread like a fluid through the sieve of larger vehicles that lacked the freedom of two wheels. A light smog filtered the sun and ensured no matter which direction you looked, you could only see so far into the fog of war. It was magnificent.

Our friend the hotel lady recommended walking along the lake in the center of Hanoi’s old town, so we crossed streets until we were upon its hazy shores. Crossing the road in Hanoi is a religious experience— you must do it slowly but intentionally, with a prayer in your heart, and is often easiest with your eyes closed. The park girding the river was filled with young people dressed in the traditional áo dài, and I approached a co-ed group taking pictures on the water. I tried English, for my Vietnamese vocabulary at this point consisted singularly of the word for ‘butthole’.

“Why are you guys wearing áo dài?” They conferred in Vietnamese for an uncomfortably long time. Eventually they procured a Google translation reading “it is tradition.” Not wanting the chat over text, I thanked them and found Andrew.

“Andrew, go ask those kids why they’re wearing áo dài!”

Andrew, equally curious, was able to dig up that it was in anticipation of Tết, the Vietnamese New Year fast approaching. Matt spotted a Uniqlo.

“Wanna bet how many times we go to Uniqlo on this trip?” I pondered five.

Jungwoo, walking a bit behind us to get reps in on his film camera, turned the bend. “Oh shit, is that a Uniqlo? Let’s go!”

After most of us were able to fill the remaining spaces in our luggage, Andrew peeled off to run errands while the rest of us made for Ho Chi Minh’s Mausoleum. The building itself was closed, so we wandered the grounds in angst. Ricky asked a soldier with a gun the size of a Labrador for a picture. The soldier said something in Vietnamese, with enough edge to be understood as ‘no’ by the most anglocentric of individuals. As the grounds began slowly closing up, we moved back downtown for an early dinner where our server Quy was delighted by Andrew’s South Vietnamese accent.

He asked us where we were all from, and was shocked to learn that we were all American— I guess a Viet, an Indian, and two white guys (to be fair, Quy said, Matt looked very European) could be an unexpected collection to all grow up in the same country. After too many beers, Andrew returned to the hotel for the night while the rest of us patrolled a local night market. The vibes were as good as the goods were bad. I fell asleep that night without delay.

Monday, January 6th

As with every good first day the starts in Asia, it began at 4am with a boundless amount of energy and a body lacking the vitality to contain it. I was pretty sure I was sick. Andrew and I headed out anyway into the predawn, circling the lake in the darkness as the worst of my symptoms faded, and just before sunrise found a back alley pho restaurant to have breakfast. We sat outside at a plastic table under a single incandescent light. Andrew explained that in the South, pho was a complicated dish with lots of additives, but in the North it was simple— noodles, broth, and some green onions. Regardless of North or South, he asserted the pho in Vietnam was the best in the world because of the freshness of the noodles. The cost came out to $2.86 USD.

Next up, we found a coffee shop and I was blown away by Vietnamese filter coffee, which had a depth of flavor that shouldn’t have made sense given its strength. Since it was a touristy, gentrified coffeeshop in the middle of downtown, my drink cost a shockingly high $3 USD.

Andrew and I sat out front on the street, watching the sun rise over the hazy lake as the once quiet road slowly populated. Andrew explained a rough outline of Vietnamese grammar at a survival level and I tried to cram as much vocabulary as I could remember into the parts of my brain that have yet to rot. By the time the others woke, I could compose enough sentences to test the patience of the remaining Viets I might encounter later in the day. Once everyone convened, we got coffee again at another shop (I wanted to see just how jittery I could get) and visited a massive statue of Lenin.

It’s strange growing up in America, where even the accusation ‘communist’ is enough to sabotage a person’s life, to see such open, proud examples in Vietnam. It made me appreciate humanity a little bit more. For better or worse, the world is not a hive mind.

Moving on, we explored the city’s citadel, which was frankly quite confusing. There’s about a thousand year gap between the youngest buildings and the oldest, and we saw a couple archaeologists poking around ruins ascribed to the Ly, Tran and Nguyen dynasties. Despite my classical archaeologist background, the younger buildings were far more intriguing to me.

There were headquarters and bunkers used by the north Vietnamese army, and the translations on the exhibits spoke proudly of fighting off the American empire (sic). My grandfather was part of this empire that invaded Vietnam, and I wondered what he would have thought about me wandering through these buildings, quietly impressed by the small nation that empires have failed to invade and control for thousands of years. I don’t know what my grandfather thought of the war. I don’t know if he truly believed America ought to weigh in on how Vietnam was governed, or whether the Gulf of Tonkin incident was a necessary evil, or really anything about him. But I sure as hell hoped my quiet curiosity was disturbing Kissinger’s ghost.

We went to a couple banh mi places for an early lunch (veg for me, non-veg for the rest) and I clocked a top 5 meal of all time. I didn’t know food could be so enjoyable. We kept wandering, somehow acquiring more coffee, and I figured I wasn’t shaking hard enough so I decided to test the Vietnamese I was learning in the field.

I approached a gaggle of women on a bridge.

“Hi,” I said, starting slow yet still botching my tones. They looked up.

“Your clothes are very pretty.”

They looked at each other in confusion. My heart groaned with annoyance and pumped harder under the combined weight of over-caffeination and the unique terror that only attractive women can procure. Suddenly, one of them repeated what I said, albeit correctly. The other two began laughing. I smiled and waved goodbye, checking my pockets to see if any dignity remained. Fortunately, for the sake of my confidence in further speaking practice, none did. Jungwoo patted my shoulder.

At this point, my sickness started to kick in to high gear so I headed back to the hotel while the remainder of our group hit up the Hanoi Hilton. I walked along the lake and saw a pair of girls wearing bright orange áo dài. I raised my hand as I passed. “Your áo dài are so pretty,” I tried again, making sure I was butchering the tones in a different way than last time. She returned fire with a smile that could execute a snowman at thirty feet. “谢谢!” She called after me, giving me a happy thumbs up. ‘中文话?’ My brain’s needle skipped tracks in its confusion with the switch from Vietnamese to Mandarin. But I had communicated successfully, so I allowed myself to feel proud on the remainder of my retreat. Andrew returned after another Uniqlo run with some Pocari Sweat and Advil.

Tuesday, January 7th

Jungwoo and I were too sick to do anything so we stayed inside while everyone else went to Ha Long Bay. I spent the day napping and reading in bed.

Wednesday, January 8th

Saying goodbye to Andrew’s hotel concierge lady, we took a bus to Tam Coc, a small town in the north that is often used as a base of operations for the very good hiking, spelunking, and ruin exploration that the area boasts. Going in with no prior knowledge, I was quite surprised to find a town almost exclusively inhabited by Europeans, where the only Viets you will find are behind the cash registers.

We put our stuff down in the hotel, a strange white building surrounded by rice fields, and Arul and I set out on a banh mi tour, tasting five different banh mi that were all incredibly mediocre. Arul couldn’t resist a mountain goat banh mi being hawked by an old man well off the main street, and his stomach couldn’t resist it either, resulting in much despair over the next 24 hours.

There was a river through town, and we hired an old lady to take us up the river in a tiny little boat, which she rowed using her feet. We basically just paddled through some rice fields, but it was pretty being surrounded by the karsts. When we arrived back in town, we found a woman on a back road renting motorcycles. I tried to ride a scooter that looked like it saw action in the Vietnam War, but quickly came to the conclusion that I was much better off navigating the potholed streets on foot. Matt and Arul arrived at the same conclusion after similar riding attempts. Jungwoo and Andrew got motorbikes, since they had a license and were eager touse it, and Ricky got a scooter. Matt pulled me aside.

“Got any bets on who crashes first?”

I pondered for all of half a second. “It’ll be Andrew or Jungwoo– Andrew will take a corner too slow and fall over, or Jungwoo will take a corner too fast and fly off a cliff. But one of them.”

Evening arrived along with our mystery illness’ symptoms for Matt, so he and jetlagged Andrew both retired while Ricky, Jungwoo, Arul and I explored the town and found a place for dinner. It was bustling, but not a single patron was Vietnamese. It followed that the food was barely edible.

Thursday, January 9th

Time passes slowest between 5am and 730am when you’re waiting for a hotel’s continental breakfast to open up. My jetlag was slowly disappearing, but Andrew’s was worsening– he’d been up since 3am.

“Andrew, your jetlag is terrible. You’ve gotta fix it,” Arul commented at breakfast.

“I don’t have jetlag,” Andrew retorted, filled with energy after sleeping the night before at 6pm.

Once everyone had made it downstairs, hopped up on dragonfruit and enough ibuprofen and cough suppressant to mask our black lung disease from Hanoi, we set out for the river in Trang An. Andrew and Jungwoo took their bikes while the rest of us hired a Grab, Vietnam’s answer to ridesharing.

“You guys should probably leave first,” Jungwoo said, “because you’ll probably be much slower in a car.”

After our Grab dropped us off, we waited 30 minutes for Andrew and Jungwoo to arrive, and then went to the docks where we chartered another pair of boats to take us up the river. This time, we passed through half a dozen caves, each one of them necessitating significant amounts of maneuvering and hunching over to avoid concussion. I didn’t make a single Viet Cong joke, despite thinking of a new one every 8 seconds.

After what felt like hours, (because it took hours, it just also felt like it) we docked, took an endless staircase up, an endless staircase down, and arrived at a pretty cool temple that had been pretty cool for the past 700 years. Andrew used his Vietnamese reading ability to read Vietnamese and explain the general history of the temple, as well as that of the Đại Việt Empire that built it.

Later that afternoon, we Grabbed to the nearby Mua Cave, which is really just a hole in a karst next to a staircase that could defeat the Dragon Warrior. We climbed to the top of the karst, where a small temple watched over the surrounding valley. The view was fantastic. The temple was crammed full of Israeli tourists, lounging on the statue, smoking, and chattering loudly. Jungwoo groaned as one of them knocked over a small jar placed before the statue. Unable to handle the secondhand cringe, we went back down.

The evening was a smorgasbord of activities– first, Jungwoo and Andrew wanted to take some pictures with their bikes. Naturally, I wanted one too. “Stolen valor!” Matt cried. “Wait– let me get one too.”

A dozen poses later, we Grabbed to Ninh Binh, the largest town in the area, which naturally is also mostly inhabited by tourists. However, unlike Tam Coc, Ninh Binh felt like a ghost town. There were tons of shops and stores along the river, but very few had many patrons. Having struggled to find filling vegetarian food, I surrendered to the allure of a pizza restaurant. Remembering my American heritage, I ordered a large for myself. It had broccoli, lotus seeds, corn, and everything else that shouldn’t go on a pizza.

Andrew tried a slice. “This is, hmm, not good. This is terrible. Why was this made? You’re on your own man, I’m sorry.” I finished the pizza alone. It wasn’t the worst pizza I’ve ever had– pizza has a fairly high floor anyways. A few beers later we called it a night.

Friday, January 10th

The hotel manager was shocked to hear that we were going to the airport to fly to Hue, a city in the center of the country.

“Why not just take an overnight train? It’s much cheaper!” he asked. Andrew looked almost embarrassed.

The ride to Hanoi’s airport was a symphony of hacking. I was coughing, Matt was coughing, Jungwoo was coughing, and Arul was coughing. But for Arul, it might have just been the mountain goat banh mi. Ricky seemed terrified, sitting quietly under his N95 mask.

At the airport, Andrew pointed out a mysterious green liquid at a shop.

“This is the Vietnamese cure for everything. You should buy this and rub it under your nose, it will clear your sinuses immediately.”

Jungwoo read the label.

“‘May cause instant fainting in children, keep out of reach.’”

I didn’t sleep on the plane due to the chemical fire in my head.

Stepping out of the airport doors and into the parking lot, Jungwoo and I immediately both pulled off our masks and inhaled. Compared to Hanoi, it was night and day. The air in Hue was breathable. It was BREATHABLE. Our hotel was about as good as the air quality. At 33 floors, it was the tallest building in the city, and it wasn’t close. Andrew and I had a suite on the 20th floor with massive floor to ceiling windows overlooking the city.

Andrew proposed we do some laundry. He handed me a drybag and told me to pack it with tshirts and underwear, add a packet of detergent, and then fill the drybag with water. After 15 minutes of soaking with periodic agitation, we emptied our bags and hung them on the clothesline Andrew kept in his pack. This minimalist, efficient style of laundry was absolutely delightful. I use a 40 gallon backpack, so I don’t need to rely quite so much on laundry, but Andrew has recently cut back to 30 gallons, and takes advantage of such tricks. I was quite impressed.

Hue is famous for its food, so we met up at a small restaurant a few blocks down the road. Like Hanoi, Hue’s traffic consists heavily of scooters doing their own thing, but the density is much lower, and crossing streets is slightly less terrifying. But only slightly. We sampled a couple different restaurants, getting a handle on the local cuisine. I will report that while the non-veg food was met with high praise, the vegetarian cuisine tasted exactly like the vegetarian cuisine I had in the north. Your mileage may vary.

Come evening, we ended up in the bar on the 33rd floor of the hotel, and I watched Matt practice his photography, Andrew pound gin and tonics, and the traffic below, twinkling to its own logic.

Saturday, January 11th

Hue has a fairly interesting history, but the most important part is probably that it was the city I was in when the Texas Longhorns played the Ohio State Buckeyes in the Cotton Bowl.

As we crossed the Hue bridge, Andrew explained the second most interesting bit of history. During the Tet offensive, the Viet Cong managed to capture the city of Hue, holing up in the citadel. The South Vietnamese and Americans spent a month working to recapture the city. At one point, the South Vietnamese made it about halfway onto the bridge to the citadel in their tanks and refused to go any further (because they were cowards! Andrew asserted) and the American marines had to crawl across the bridge themselves under heavy fire to destroy the Viet Cong artillery positions, collectively earning several Medals of Honor in the process.

The citadel itself was quite incredible. There were dozens of buildings used by the Nguyen dynasty in some Forbidden City analog, and I had a nice morning wandering the grounds and exploring the gardens as Matt and Ricky holed up in a corner to watch the Longhorns lose tragically.

“Where did those two go?” Arul asked.

“They’re like cats. They go find a quiet corner when they’re ready to die,” Andrew answered.

After the coffee cravings became too much, we left the citadel. Or at least tried to. Jungwoo, Arul and I spent 20 minutes arguing about how to get out, wandering down corridors and between buildings towards a very inappropriately placed exit. My pathfinding philosophy largely boils down to ‘eh, better to commit to a random direction than be still for more than 10 seconds,’ which makes me seem extremely confident to the detriment of those who think I know the slightest bit of anything. After enough wrong turns, Arul was able to see through my guise to the underlying idiocy and logic our way to freedom.

The coffeeshop Andrew led us to was in a quaint little garden, and we posted up under a tin awning and discovered egg coffee. Vietnamese coffee is a little like getting your tongue stepped on– it’s probably the strongest coffee I’ve ever had, and makes me ashamed to call myself a black coffee enjoyer when I can barely tolerate the Viet variant neat. The counterplay to that bitterness is the addition of eggs, which give it a deep, sweet creaminess that worked quite nicely with the coffee. It began to rain, rattling against the tin awning and rivering through the flowerbeds, but with my warm coffee in my hands I was perfectly content to enjoy the quiet afternoon.

When the rain finally died down to just a downpour we accepted our damp fate and visited a nearby shrine. I found Jungwoo and Arul hiding underneath the temple roof.

“Hey, you know that monk that set himself on fire? He had a famous picture?”

“Yeah.”

“His car is back there.”

“...his car?”

“Yeah his car.”

“Why would his car– why would he have a car? You’re fucking with me. I’m staying here where it’s dry.”

“No no, his car is back there.”

“He’s a Buddhist monk, he wouldn’t own a car. That’s like, against the concept of Buddhism, to own a car.”

“Okay fine. Don’t go look at his car.”

Begrudgingly, both followed me around the corner where that monk’s car was parked in a garage.

“Huh. Why did he have a car?”

“Beats me.”

Sunday, January 12th

The next morning we packed our bags, and headed down to the lobby where we were dejectedly met with rain splattered windows. The pluvial mood was in stark contrast to that of the four motorcyclists waiting to accompany us to Da Nang. After checking out of the hotel, they took our bags, wrapped them in plastic, and helped us mount up. Andrew and Jungwoo rode by themselves, being licensed and brave, while Arul, Matt, Ricky and I each rode double with one of our guides.

The rain had washed away much of the pollution and the cool morning air tasted crisp and delicious as we rode along. I’ve never had much interest in motorcycle riding, but it was genuinely a very nice experience. I was incredibly worried for Jungwoo and Andrew, but things seemed to be fine so I tried to focus on enjoying the moment. We made a couple stops that morning. We saw a bridge slightly older than the United States, and we visited a wet market where I was quite certain the next Covid-19 was incubating. We took a cigarette break at a fishing village, where Jungwoo and Andrew partook, and I entertained the idea for a moment but eventually decided to keep my recovering lungs clean, before making another stop at a waterfall running over a sheer rock face. For lunch we stopped at a rickety wooden restaurant perched precariously above the ocean, and then we were off again.

The approach to Da Nang necessitated a climb up over a small mountain, and several switchbacks going both up and down. On the first switchback, everyone took the turn wide, except for Andrew, who took it tight. From the corner of my eye I watched him try and catch himself with his feet, stumble, and fall, the bike coming down with him. In an instant, all four professional motorcyclists were off their bikes and converging on him. The only damage was a scraped hand, which they washed with a bottle of water. One of them took out a cigarette.

Jungwoo and I exchanged a glance. “Guess they have to cauterize it.”

Andrew looked dismayed and winced at the expectation. However, instead they split the cigarette opened and rubbed the tobacco on his palm, causing the wound to clot immediately.

We continued onwards, this time much more slowly, as each driver watched Andrew like a hawk. We went up through the mountain pass, and then back down, coming into Da Nang and driving along the coastline. At a stoplight, my driver pulled up immediately next to a girl on a scooter, probably a few years younger than me. He stared at her and she awkwardly tried not to make eye contact. Eventually she conceded to his gaze, and looked up. He gave her a thumbs up. Confused, she returned the gesture. He extended his fist. She tapped her own against his. He then patted my leg, and gestured towards the girl. I pretended to be fixated on something on the opposite side of the road. After several years, the light turned green. We drove on.

Our penultimate destination on the bikes was the statue of the Lady Buddha on the far side of Da Nang. The temple grounds were lovely, and I enjoyed listening to the mantra chanting inside. Buddhism is wildly different in every implementation, and this flavor was nothing like the silent Buddhism I’d encountered in Japan.

As Jungwoo and I exited the temple, Andrew and Arul suddenly appeared. “Race war! Race war over there by the bathrooms! Hurry!”

Jungwoo and I rushed in the indicated direction where we stumbled upon some dogs barking at some monkeys. It felt like something out of a Japanese folktale. A throng of Koreans were excitedly filming and taking pictures.

Finally, we finished our journey at our hotel right on the ocean. We gave our valedictions to our guides, checked in, and Andrew went off to see his family, as he was a Da Nanger by blood. Matt went to wander on his own, and the remainder of our group found a brewery down the road on the beach. We camped for a few hours, pounding beers and watching the ocean.

The six of us converged later for dinner at a restaurant chain recommended by every Vietnamese expat– Pizza 4Ps. The menu humbly asserted that one pizza could feed two people. Naturally, we ordered six pizzas. The waitress looked more and more distressed as our order grew.

“Look Zach,” Arul said, excitedly pointing at the menu. “They have a five cheese pizza. That’s better than a four cheese pizza. It’s much better than a three cheese pizza. But they have another cheese you can add to any pizza listed right here– dare I make a six cheese pizza? Will my ambition be rewarded, or will it be my downfall?”

After we finished all six pizzas we called her back over. “Are you ready for the check?” she asked. “Not yet,” Arul replied. “We’d actually like to order more pizzas.”

Monday, January 13th

Andrew’s cousin very graciously offered to ferry us around all day, and so he picked us up early from our hotel to take us to some interesting places around Da Nang. Our first stop were the Marble Mountains, a cluster of five hills with some interesting temples and pagodas decorating their summits, as well as some Buddhist and Hindu grottoes. One of the grottoes had a high ceiling, a lovely Buddha statue, some incense, and the serene, constant drip of water echoing gently from some corner. I thought about lighting some incense and offering a prayer. Matt appeared behind me.

“Apparently this was a Viet Cong hospital during the war.” I elected to not offer a prayer.

From the Marble Mountains, we set out for My Son, a massive complex of Hindu ruins left by the Champa kingdom. The Dai Viet was the northern kingdom, while the Champa controlled the south, slowly losing territory to the Dai Viet. I personally find religious syncretism extremely interesting, and as a former archaeologist, I was giddy with excitement to visit this outpost of Hinduism all the way out in Indochina. Unfortunately, the Viet Cong tried to use the ruins as a base during the war, and subsequently the United States bombed the site, damaging it significantly. If people are going to kill each other, that’s their business, but I would prefer if they didn’t fuck up the local archaeology.

Andrew’s cousin dropped us off in Hoi An, a small town south of Da Nang, where we intended to spend a night in order to appreciate the lantern festival. I was excited. I asked Andrew if he was excited.

“Can’t wait to watch people pollute the local river with garbage lanterns.”

I don’t think Andrew was excited.

After several banh mi and a sunset, the festival came alive. Stores and bars along the banks hung lights outside and in the trees, and the river was crowded with hundreds of small boats. Vendors along the river sold little paper lanterns with enough capacity to hold a candle, asserting that casting one into the water would bring a year of luck.

Andrew and Matt seemed a bit disgusted with the whole operation, calling it gimmicky and touristy, but I found everything delightful. Festivals always illicit a lot of emotion from me– as someone who lives in a quiet suburb, unable to recognize a single neighbor, the concept of community events and being around other people is charming and idyllic. But at the same time, it’s somewhat lonely, knowing that by appreciating the painting you’re not part of it. It’s a complicated feeling.

I fell asleep to the sound of drunken revelry beneath my window.

Tuesday, January 14th

Our time in Central Vietnam finished, we returned to the Da Nang airport to catch a flight to the final city in Vietnam we would visit– Saigon. Ricky had to check in at the counter because he didn’t have his middle name on his boarding pass.

Ha, rookie mistake, you need to learn how to navigate the bureaucratic nonsense, I thought, as I went straight to security.

The security guy looked at my passport and boarding pass. “I’m sorry, I can’t let you go through. You don’t have your middle name on your boarding pass.”

Wow, what an oppressive country, nobody is safe from their bureaucratic nonsense, I thought, as I left security to amend my mistake.

On the plane, I sat next to an elderly Japanese man.

“Here we go,” I said in Japanese as we took off.

“Ah, you speak Japanese! Why is that?”

I didn’t want to tell him that it was because I am a huge fan of the 60s children’s TV show ‘Ultraman’.

“My grandfather was a Japanese,” I lied.

“Oh, I thought it was because you are a fan of Ultraman,” he said, gesturing at the Ultraman shirt I forgot I was wearing.

“Do you like Ultraman too?” I asked.

Wordlessly, he reached into his bag and pulled out his keys, with a small Ultraman figure hanging from the keyring.

We spent the next hour chatting about Ultraman, as he remembered watching the original show as a child. He pulled a notebook from a pocket and drew several of his favorite monsters, telling me stories about pretending to be those kaiju while playing with his friends. Even though he kept his Japanese simple, I still managed to lose comprehension several times, but followed along thanks to his illustrations while he spoke. When we landed, his wife approached down the aisle from several rows back.

“Dear, this guy is an Ultraman fan! Look!” he moved my jacket to display my shirt better.

“My, that’s very nice you’ve made a friend.” She responded with a small smirk.

“He’s not just an Ultraman fan, dear, he’s an Ultraseven fan!”

I nodded politely to his wife.

When we arrived in Saigon, it was raining pretty hard. Hotels in Vietnam provide you with a drink while you wait in the lobby– our hotel in Saigon procured coconuts and straws.

“This is the best welcome drink yet,” Ricky muttered as he drained his coconut.

Once the rain cut back to a manageable amount, Andrew and I hit the streets as he gave me a quick tour of the area. He pointed out various hotels and buildings that were relevant during the war, and we went inside a mall that had once been the American embassy from which that famous helicopter picture was taken.

Saigon has a very interesting vibe to it. More than any other city in Vietnam, it has a colonial vibe left over from French occupation that can be felt in the broad, palm lined streets and a lot of the architecture downtown. Traffic is just as bad as anywhere in Vietnam, but because of the wider streets, it felt a lot more dangerous and harder to cross the road. The people seemed a lot more laid back here too, wearing shorts (it was 90 degrees Fahrenheit and 100% humidity, shorts are a necessity) and many sporting dyed hair. I realized that my favorite city in Vietnam was consistently whichever city I was currently in. Except Tam Coc. I am not a Tam Coc enjoyer.

After night had fallen and Andrew and I were fed, we met up with the others at a steampunk cocktail bar. Drinks were delicious, albeit American priced. I ordered one of their specialty cocktails. It came with a sausage garnish. Matt found this hilarious. “I can’t believe you found the one cocktail in the world that isn’t vegetarian.”

Wednesday, January 15th

I woke up tired and hungover, so I thought I’d find some coffee. I picked an arbitrary direction and slogged through the morning humidity for about 45 minutes, nearly dying to traffic several times. I approached an elderly woman sitting in front of a cart of fruit. One of the chief virtues of the Vietnamese seems to be owning a small business. Everyone has some kind of restaurant, or food cart, or massage parlor. Nobody ever seems to work for someone else.

“Coffee? Cafe?” I pointed in a few different directions to indicate I was asking where.

She stared for a moment at the idiot American before pointing down a cross street.

“Thank you!” I repeated in both English and Vietnamese, and crossed the road. I was almost hit by four different vehicles, and yelled at by one driver. I imagined what the old lady was thinking. Idiot American, probably.

Having crossed the road, I came across an open door, so I went inside. The whole place felt straight out of the 1950s, with dark wood paneling, a few old radios, and a CRT TV set. I didn’t see anyone so I walked towards the next room. A man emerged and said something in Vietnamese. He seemed confused and defensive.

“Hello, is this the cafe?”

He spoke more Vietnamese and gestured towards the door.

I started backing up. “Um… coffee?”

He stopped speaking for a minute and cocked his head. Then he walked past me, gesturing me to follow. We went across the street into a building that, once inside, was clearly a cafe. He spoke to the woman behind the counter and I realized I was probably just traipsing around in his house. Oops.

I sat down at a table by myself. I didn’t need to specify that I wanted ice coffee, and that’s what she brought. It was only 8am but 85F, and the humidity was indescribable. A few bikes hummed by down the narrow street outside and the woman took a brief call, laughing quietly in the corner before returning to her post at the counter, lazily leaning against it and scrolling on her phone. I finished my coffee and paid, thanking the woman, and I returned to the street.

As I walked back towards the intersection where I’d almost died (or at least the most recent one), I passed the man’s house I had trespassed into. He came outside and looked me up and down.

He spoke in rough English. “You want see… bunker?”

Hell fucking yes I wanted to see the bunker.

“Yes,” I answered. “Yes.”

The man slid the coffee table in front of the couch back and pointed at the floor. I looked at him uncertainly and he continued to point. Noticing a small groove between the tiles, I pulled on it to reveal a hole in the floor. He was still pointing. I went into the hole.

I found myself in a tunnel carved through the rocks, lit by low lighting. There were two rooms branching off from the tunnel; I checked them both. More artifacts of the ‘50s and ‘60s, as well as a portrait of Ho Chi Minh on the wall. At the end of the tunnel was a ladder. I climbed straight up. It took me to a crawlspace in the wall on the second floor of the house. The upstairs was nice. Another TV set, some chairs, a bed, a toilet, a balcony. I took a few photographs before going downstairs. I thanked the man and left.

With some coffee in me, I walked back to the center of the district and found the War Remnants Museum. I was seduced into buying a ticket by the Chinook on the front grounds. Nobody can resist a Chinook.

The museum was impressive as well. I am always intrigued by war museums in other countries and the perspectives they bring. History isn’t written by the victors, it’s written by the museum hosts. This museum focused heavily on the war crimes that the Americans committed during the Vietnam War. I didn’t mind too much, as we learned about the war crimes the Viet Cong committed in school, and I would never insist on a black and white narrative for any war. That being said, I particularly enjoyed the war photography in the museum, despite it being rather gruesome.

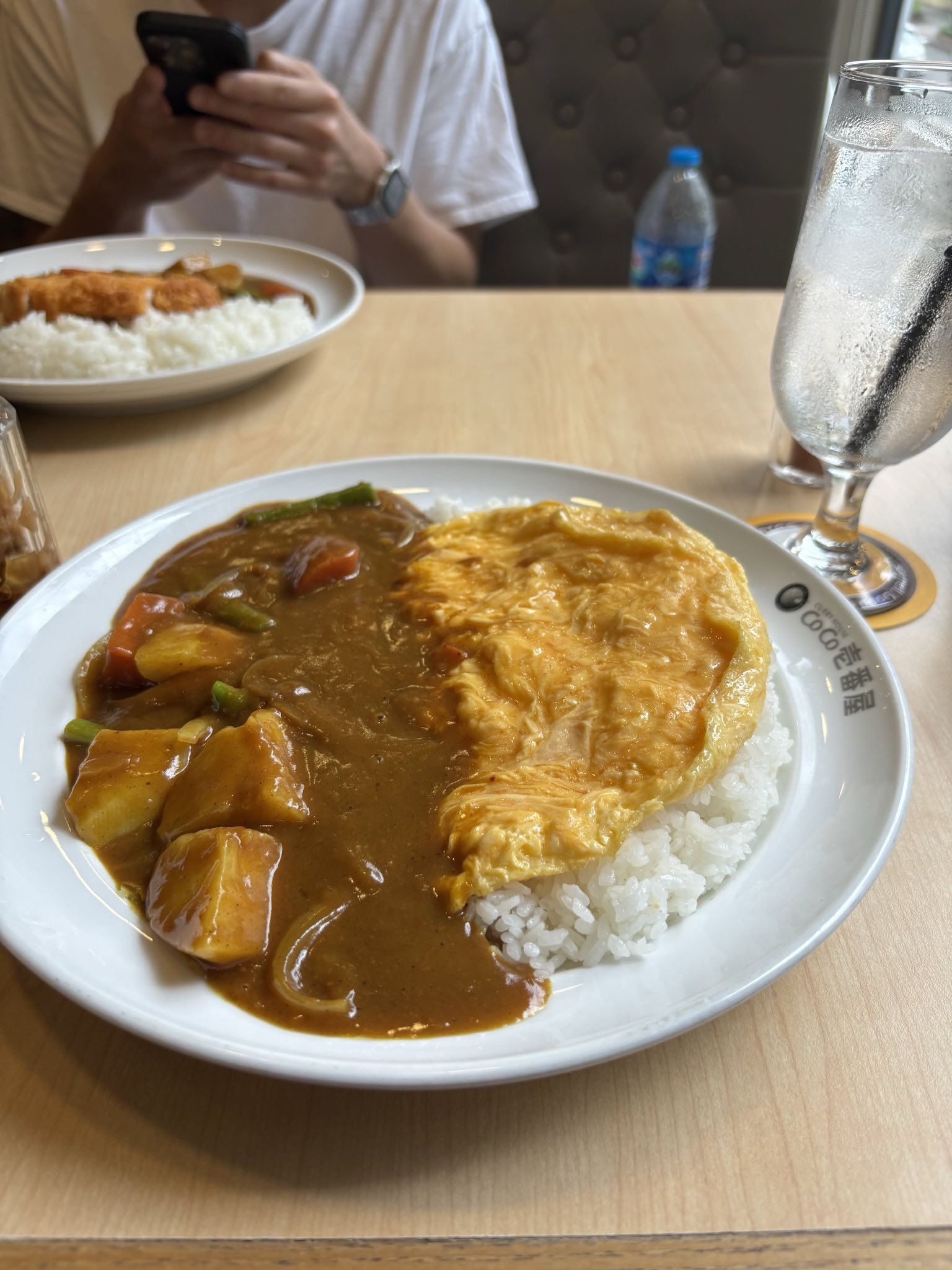

Jungwoo and Ricky happened to be a floor above me in the museum, and when they finished up we went to Coco Ichibanya for lunch. I’m gonna keep it a buck fifty– of all the restaurants on the planet, the only one I care about is Coco Ichibanya. It’s a Japanese curry chain that I went to ten times in the two week period I was in Japan, and I was not about to pass up the opportunity in Saigon. It was delicious. It’s always delicious. Go to Coco Ichibanya.

The evening passed without much to note. A brewery, a restaurant, a festival, and an early bed.

Thursday, January 16th

Our travel day began with Arul taking me at a pace a weaker man would call a jog down the street to grab a kilogram of coffee beans, something I wanted to take back for Surya. Then we headed to the airport.

The Saigon airport is not an efficient place. We waited in line for almost an hour to get our boarding passes (stupid middle name correction) and then spent another hour in line at immigration to get stamped out of the country. Then we meandered through security, and emerged on the other side with a solid three minutes before our plane began boarding. I worry about everything. I worry about things that might happen, and I worry about things that have already happened. Naturally, Saigon airport gave me ulcers.

After we landed in Taiwan, took the train to our Airbnb, and washed up, we pressed heel to pavement and headed for a local night market. It was packed with people and food stalls, all shuffling slowly down each aisle as vendors advertised their snacks in Mandarin. I joined the line and shuffled into the fray.

After taking 10 steps (or 5 minutes of walking, whichever measurement you prefer), I was slapped across the face with the acrid smell of vomit. Immediately, I was overwhelmed with nausea. I tried to discern where the vomit was on the ground– with people this tightly packed, it was very possible that I’d have to be very careful moving around it. But no vomit appeared. And then I realized. The smell was not from human upchuck– it was stinky tofu. I’d never smelled such a rancid food. I walked over to the stall.

“I’d like a small stinky tofu,” I asked in Mandarin, handing him a few coins.

He put some stinky tofu into a box, and I carried it to a quieter sidewalk to eat. It looked exactly the same as regular tofu, it just smelled like barf. I chewed it thoroughly. It actually wasn’t bad– it was warm, and had that ideal tofu balance of crispy on the outside and soft in the middle, and it had some flavor. That flavor happened to be bile, but it was still a flavor. 6/10. Not terrible.

Next up I located a purveyor of spring onion pancakes.

“You want spicy?” he asked.

“Of course I want spicy,” I replied, hoping he could understand my genuinely awful accent. He began making it, and I watched.

“Excuse me, is that a hair?”

He didn’t react. I wondered if I used the wrong word for hair. The silence was painful. Then he brushed it away. “35 yuan,” he said.

I paid him and he handed me my pancake. It was admittedly pretty good. I tried not to think about the hair.

Matt appeared. “Boba?”

“Boba.”

We got boba. Milk tea in Taiwan is deservedly hyped. The pearls are exactly what you’d hope for– consistent, far more flavorful than those found in the United States, and had a good, firm chew. Soft pearls are always so disappointing. The drink was more milk heavy, which I was a little disappointed by, as I prefer a more teay tea. But it was well within the domain of deliciousness.

There happened to be an izakaya nearby, so all parties converged and we ordered a round of Asahi. The waitress returned after a second.

“If you want, instead of bringing out individual rounds, we could provide you with a three liter tank of beer.”

Andrew nodded.

“That seems incredibly wise. Bring us a three liter tank of beer.”

Andrew’s wisdom did not extend to pouring beer, unfortunately, and Jungwoo was forced into the role of distributor to ensure we all had a properly sized head. The tank lasted 10 minutes. Andrew flagged the waitress back over.

“Excuse me, could we do this again? But with, erm, highball this time?”

The waitress, noticing the tank was suddenly empty as she heard the request, looked like a deer caught in headlines.

“Uhm… sure… but you do know that highball is rather… stronger than beer?”

“Oh yes, we do know, that’s why we’re ordering it. Is that okay?”

She nodded and carried the tank back into the kitchen. Through the curtain, you could see her dumping a plastic liter bottle of whisky into the tank. Was it glorious? No. Actually, it seemed quite degenerate. She brought it back out and Jungwoo distributed another round.

By the time we cleared the second tank, everyone except for Ricky was quite wasted.

“This is disgusting,” Ricky kept saying. “It’s so much liquid. How can you guys drink this? Let’s just do shots guys, come on.”

But nobody really heard him. Andrew continued to order food, and as the ABV rose the more he tried to make things easier for the waitress. Andrew is what you would call a considerate drunk.

“Excuse me, erm, I’d like to order food. What is the easiest thing on the menu?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Like, what is easiest for you to make? We don’t want to be a bother, you see. So I want to order something that isn’t annoying for you to make.”

“Oh… uhm… maybe, this?”

“Okay, that’s, that’s– that’s good.”

We paid, and staggered onto the street. I tried very hard to remember the order in which my feet should be placed in order to ambulate in a direction. Andrew and Arul seemed like they were going to keel over. I wondered which would vomit first. We found a 7/11 somehow. Polite society prevented Andrew from entering.

“Jungwooooooo! I need… pockery!”

“What the hell is pockery?”

“Pockery man, pockery! I need the… the electrolytes.”

“I don’t understand you. What the fuck is pockery? Pocari? Pocari Sweat?”

“Yeah, get me some pockery! And some water. And something to eat. Can you get me spaghetti? I want to eat spaghetti. And don’t forget the.. the pockery!”

Everyone emerged with at minimum, a liter of water and a sports drink, with Jungwoo carrying Andrew’s offerings as well. Ricky was holding a small bottle of whisky, sipping from it.

“Have some,” he kept repeating, thrusting it towards whoever happened to walk nearest to him. Nobody accepted. Another droplet of alcohol would have sent the camel to the chiropractor.

“Did you get my… pockery?”

“Stop saying that,” Matt said. “Pockery sounds like a Biblical sin.”

Friday, January 17th

The sun cruelly woke me up at 7am the next morning with a wicked hangover. Compared to the others, I didn’t drink nearly as much, but with a 40 pound shortage of bodyweight, I didn’t feel that lucky. I stumbled out of bed. Andrew was wide awake and dressed.

“Morning. I just came back from shopping. I also picked up our Taipei FunPasses. I’m going to go look for some coffee and breakfast, wanna come?”

I squinted and tried to allocate some of the energy that I was using to not fall over towards replying.

“...Let me get ready. Five minutes.”

Ten minutes and two ibuprofen later (I really owed Andrew my weight in ibuprofen at this point in the trip), Andrew was directing us through the underground maze of the subway station, passing a convenience store (ah, the ichor, the lifeblood of man, Pocari Sweat) and emerging in a park. A few streets later we found a tiny garage where a Taiwanese man and woman were busy cooking.

“Can we get two spring onion pancakes?”

The woman smiled maternally and a few minutes later, we were walking back to the park. There were few things I’ve eaten in life quite as delicious as that spring onion pancake. It was warm, crisp and flaky, with a robust flavor, and soaked up all of the blech from the night before. Few meals have ever left me so satisfied.

Andrew looked at his empty box. “I could eat four more.”

“No you couldn’t.”

We went back and ordered four more. The woman looked dubious, but amused. Andrew finished three. I was still impressed.

We Ubered to the National Palace Museum. The museum is massive, and the amount of content is comical. We took the first floor slow, admiring everything and reading each description, but by the top floor I was basically skimming everything. At some point, I managed to lose Andrew but found Jungwoo, Arul and Ricky.

Taiwan has a couple national treasures, two of which include the fabled Jadeite Cabbage (a piece of jadeite carved to resemble cabbage) and the Meat Stone (a piece of jasper carved to resemble pork belly.) Neither of them were available.

“Can you image,” Jungwoo asked me. “When all this shit was being evacuated from China, being a Taiwanese soldier told to risk his life to recover the Meat Stone?”

After a surprisingly mediocre lunch at Din Tai Fung, we came out of the subway at Taipei101, young Zach’s favorite skyscraper. We took the elevator up to the observation deck on the 89th floor (the 101st floor was booked out for the day) just in time to catch the sunset.

Saturday, January 18th

First a train and then a bus took us to Jiufen, a small village directly northeast of Taipei. Jiufen is famous for supposedly resembling the downtown in Miyazaki’s Spirited Away, and so a lot of tourists visit to enjoy its hiking and teahouses. We were not special. After arriving at the base of Teapot Mountain, a mountain that looks like it has a teapot on top (good job, Taiwanese mountain naming team!) Andrew tapped out, saying he felt sick and wanted to go back to Taipei. The five of us remaining set out, eventually arriving at a Shinto Shrine.

“We are not on Teapot Mountain,” Arul said, pointing at Teapot Mountain.

“God dammit,” Matt said.

After ascending, we found the path to Teapot Mountain, but Ricky and Matt decided they’d rather drink tea and hang out with cats instead of climbing Teapot Mountain. So Arul, Jungwoo and I bravely set out alone. To climb Teapot Mountain. If you didn’t catch that.

The hike to the summit was not too bad, and afforded a ton of gorgeous views of the ocean and surrounding mountains. Jungwoo, a mountain goat at heart, managed the final scramble to the spout of the teapot, where he posed as a little teapot, short and stout (naturally) while Arul and I found a nice vantage to take pictures. We descended.

We wandered the main street for a while and I saw an alley.

“What a beautiful looking alley,” I said, with absolutely no desire to go down that alley.

“Let’s go down that alley,” Jungwoo replied.

We went down the alley. This was Paco’s alley.

Paco was an elderly man who sported the only open door in the alley, behind which stood a small room filled to the brim with the fruits of his artistic vision. Thousands of photographs he’d taken over the past 40 years, as well as stacks of watercolor paintings, cluttered every available surface of the room.

We entered. He said something in Mandarin that I didn’t catch.

“My Chinese isn’t very good,” I responded with my characteristic rough grammar.

“My English isn’t very good,” he smiled, using the exact same incorrect sentence structure I did.

That was a lie– his English was more than enough to talk quietly and wistfully about every single shot he’d taken, as one look at a photograph was enough for him to procure the story behind the composition, as well as the camera he’d used, and when he’d developed the film.

A modern Medici, I funded Jungwoo’s purchase of a black and white photograph of a young man and woman standing on a Jiufen terrace, overlooking a stormcloud.

Paco looked at Arul next, understanding he was on the verge of making a second sale. “You guys are American? I don’t believe it! You’re not fat enough to be American!”

Arul smiled and made a purchase as well.

At the highest point in town, we found a precarious teahouse, built entirely of lumber that seemed to creak and bend as we climbed its steps up to the third floor. We ordered a charcoal oolong tea, and sat against the banister, looking out on the town, mountains and ocean. The proprietor brought us a huge kettle of boiling water, as well as the tea leaves, and a few smaller vessels. He demonstrated the traditional method for brewing tea in Taiwan. It was wonderfully elaborate, from using hot water to warm all the vessels, to having separate cups for drinking the tea and smelling the tea. We sat and drank tea, watching the town below, until each of us had consumed sixteen cups of tea.

The bus back to Taipei was something of a nightmare. Having consumed sixteen cups of tea, I had a strong urge to urinate. Yet the gods of Taiwan had other plans, namely ones that involved severe traffic. My 26 year old bladder and sense of social respect were enough to hold on. The elderly Chinese tourist behind me, however, lacked both of these critical elements.

My phone lit up in the dim light of the bus. It was Jungwoo. ‘Don’t turn around.’

Suddenly, I heard a gentle moan, and the sound of a liquid stream echoing against the wall of a plastic container three inches behind my head. I prayed for death. My phone lit up again. ‘It got on your seat!’ I prayed for things worse than death.

When the bus arrived an hour and a half later, I staggered out and set a non-negotiable course for the nearest Coco Ichibanya. The bathroom there was civilized, and the food was delicious. There is nothing on earth better than Coco Ichibanya.

Sunday, January 19th

To paraphrase Raymond Carver, I woke up to the sound of rain and felt a terrific urge to lay in bed all day. Matt asked if I wanted to go hiking on Elephant Mountain. I made eye contact with the rain, to the best of my ability. I didn’t blink. Matt set out on his own. I closed my eyes again.

Once the rain had died down, Jungwoo, Matt (he was a fast hiker) and I took a series of trains to a gondola station in the Taipei Zoo, where we rose through the low hanging clouds still pregnant with rain up to a tea plantation.

We had some tea (ever the contrarian, I had some much craved coffee) and wandered around the mountainside. People moved slowly. The hills below us were green and terraced, and the air smelled incredibly clean. In the distance, Taipei101 poked through the clouds.

“If this view is all I see today, it will still have been a good day,” Arul said.

We took the gondola back down.

With our transpacific venture in a few hours, everyone had their final items to close out before heading to the airport. I had nothing in mind, so I tagged along with Jungwoo. He picked up some pineapple cakes from the mall inside of Taipei101, and then we took the subway to the Ximen neighborhood for a last meal. Naturally, it had to be Coco Ichibanya.